Review: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

Sitting in my Lowry chair, I reflected on the broad appeal of the play I was about to see. The theatre was filled, with an audience much more diverse in terms of age than I was used to seeing. The penultimate evening of a UK tour which, by all accounts, had seen such huge numbers every day. And the pull of this play is not just national, as the tour is next heading across the pond, to hit Broadway. My expectations were naturally high.

Sitting in my Lowry chair, I reflected on the broad appeal of the play I was about to see. The theatre was filled, with an audience much more diverse in terms of age than I was used to seeing. The penultimate evening of a UK tour which, by all accounts, had seen such huge numbers every day. And the pull of this play is not just national, as the tour is next heading across the pond, to hit Broadway. My expectations were naturally high.

I had been diligent with my research surrounding the play I was about to see, so I had already read the book on which it was based. Mark Haddon’s award-winning 2003 book had charmed me with its portrayal of Christopher Boone, a narrator somewhere on the autistic spectrum, who embarks on a detective enterprise following the murder of his neighbour’s dog. The first person narration of the book allowed me to empathise with Christopher and understand his perspective in a way that I feared a play would not, so it was with eager curiosity that I settled down to watch.

What happened next was truly amazing. Where the book had led me to understand Christopher’s world, the National Theatre’s production led me to feel it. Scenery, props, and soundtrack were all drafted in to assist with the creation of a whole world on stage; the world inside the protagonist’s mind. The acting space itself was turned into a neat cube complete with grid lines, to reflect the importance which mathematics played in Christopher’s world. This space was then transformed into: a single house, a row of houses, a train, and a London street, all seen through the eyes of Christopher Boone. To achieve this, a whole range of stage trickery was employed, from low tech props such as a children’s train set, to a digital edge being introduced to create drawings on the walls and floor, to a little live puppy being brought onto the stage. The first half closed with a toy train moving off along a track which had been built as the action progressed, perfect in miniature.

What happened next was truly amazing. Where the book had led me to understand Christopher’s world, the National Theatre’s production led me to feel it. Scenery, props, and soundtrack were all drafted in to assist with the creation of a whole world on stage; the world inside the protagonist’s mind. The acting space itself was turned into a neat cube complete with grid lines, to reflect the importance which mathematics played in Christopher’s world. This space was then transformed into: a single house, a row of houses, a train, and a London street, all seen through the eyes of Christopher Boone. To achieve this, a whole range of stage trickery was employed, from low tech props such as a children’s train set, to a digital edge being introduced to create drawings on the walls and floor, to a little live puppy being brought onto the stage. The first half closed with a toy train moving off along a track which had been built as the action progressed, perfect in miniature.

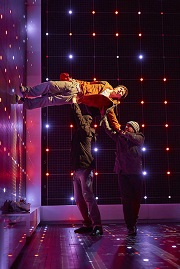

The theatricality of the performance in terms of ‘techiness’ was perfectly complemented by the sparing use of props, paving the way for some spectacularly agile displays of physical theatre. Joshua Jenkins, in the central role of Christopher, matched his powerful acting with an equally striking acrobatic ability, giving us the impression that walking at 90 degrees to the floor was a normality for him.

The theatricality of the performance in terms of ‘techiness’ was perfectly complemented by the sparing use of props, paving the way for some spectacularly agile displays of physical theatre. Joshua Jenkins, in the central role of Christopher, matched his powerful acting with an equally striking acrobatic ability, giving us the impression that walking at 90 degrees to the floor was a normality for him.

Joshua Jenkins’ performance was extremely special by any standards, and it was not the only outstanding display of acting in the production. Every character was superbly portrayed, from Christopher’s often harried parents, through to the head teacher at his school, who, despite having only a few lines, made the audience laugh for a good minute each time.

And there was, perhaps surprisingly, a lot to laugh about. Although the play is essentially about the difficulty of surviving in a world which everyone sees differently to you, under Marianne Elliott’s direction, we were shown that there is humour to be found in almost every situation. As Christopher sets out on a journey which takes him from his own road all the way to London, the furthest he has ever been, the way is fraught with both misunderstandings and revelations, many of them gently humorous.

As an audience member, I can only hope that the play’s own journey to America, though a little longer than Christopher’s, ends in exactly the same way. With a triumphant return home to England, and to the Lowry theatre.