Never Judge A Book By Its Cover

Anyone who has been an M&D family magazine reader for any length of time is certain to have come across at least one article written by Mike Stevenson, one of our oldest contributors. While perusing his articles, one word is sure to have been flashing in your head. That word is teacher. His articles are very informative, focus on the development of creative thinking skills in children, and are often stuffed full of facts. If ever it was possible to ascertain someone’s calling in life just from their written style, it is possible with Mike Stevenson.

Anyone who has been an M&D family magazine reader for any length of time is certain to have come across at least one article written by Mike Stevenson, one of our oldest contributors. While perusing his articles, one word is sure to have been flashing in your head. That word is teacher. His articles are very informative, focus on the development of creative thinking skills in children, and are often stuffed full of facts. If ever it was possible to ascertain someone’s calling in life just from their written style, it is possible with Mike Stevenson.

And, indeed he is not just a teacher, but an educator. He has taught in secondary schools, became Head of an experimental primary school, worked as a Local Authority Advisor and an Ofsted School Inspector. I thought, just from reading his articles, that I had this man completely pegged.

And then, following a recommendation for an entertaining read, I discovered his e-book on Amazon. I looked at the title, and realised that I had probably been wrong about Mike Stevenson. A book called “Do Yer Do Nudes, Sir?” is not the sort of thing you would expect a well-behaved teacher to write. But as it turns out, he didn’t begin as a teacher. He started life as an artist, training at the Liverpool College of Art. 004282

Michael Stevenson is 3rd from the left

Mike Stevenson fell into education completely by accident, as is detailed in the opening sections of his autobiographical book.

“You know what we should do?” I asked him.

…I paused to make sure I had his attention. “One of us could get a job”. Tony leapt to his feet, pointing an accusing finger at me. His voice cut through the general chatter of the pub in a tone of righteous indignation. “This man has made an obscene suggestion to me!” he shouted, the whole of his body trembling to portray the shock he felt. “He has suggested that I work for a living!” The regulars in the pub were mostly students, tutors, and models from the College of Art, and were quite used to Tony and his outrageous outbursts.

… “Listen and be serious,” Tony admonished, “There’s a job in the Echo”. He scrabbled around on his bed, finding the evening newspaper he wanted and searching though it to find the part he wanted. “Look here,” he pointed, “This school, Failsworthy Secondary Modern, wants an art teacher”.

“I’ve never taught anyone anything in my whole life,” I protested. Tony looked at me with his sensible expression. “It’s £760 a year,” he said ruthlessly.

“Heroes? Time? You are…er…employed here to teach…er…art. Other teachers will …er…teach history and mathematics. I have already established that you are at best mathematically…er…incompetent and now I find you neglecting your duties in order to pass your incompetence on! You will stop this immediately. Teach art…er…that’s what you are here for and…er…start now!”

…I stood in Denise Drew’s office.

“Wow”, she said, “I could hear every word out here. You’ve managed to get yourself in big trouble very early in your career, haven’t you?”

It is also a very insightful look into education in an inner city school in the 1960s. There are certain aspects of the book that everyone can relate to, looking back at their own days as a student.

I opened the door to reveal the members of 4C slumped against the walls and banisters in poses redolent of sullen, teenage cool.

This is what he had to say about his childhood memories: “I believe my life was changed radically by reading. I come from what would now be described as a deprived background. I can’t remember not being able to read. At infant school I was the first to finish the graded reading scheme and in those days that meant being taken to the local library and presented with a free library ticket. I chose the thickest book I could see as we had no books at home. It turned out to be a compendium of schoolboy adventure stories set in boarding schools, and I read it avidly. When the opportunity came for children of seamen killed in shipping accidents, (as I was) to attend a boarding school, I volunteered immediately and went away from home at the age of eight until I was thirteen. Those years opened my eyes to different ways of life than that experienced in Liverpool 8! Horizons widened and possibilities existed that I would never have dreamed of because of that experience. So words and books were very much a part of my life from the very beginning.”

As well as working in education for most of his life, he has never lost touch with his creative side, and this has allowed him to now sit down and write a book.

Mike Stevenson on the subject of beginning the writing project: “If you are familiar and comfortable with books then the transition from reader to writer isn’t such a huge one. When I retired I decided to find out if I could write a book. So I did! I simply decided that for 3 hours every morning I would write. After three months there was a book.

I think if you have a background in art you are used to the fact that you are constantly finding out how and what you can do. Problems arise for people who want a guaranteed end product before they start, as they forget that any creative act is an act of discovery. I didn’t know how to write a book, but I learned how I wrote my book in the process of doing it.”

So how does he himself reconcile these two seemingly differing sides of his character, illustrated by two very different writing styles?

This is what he has to say on the matter: “I think I would have to describe myself as a teacher rather than an artist. I always managed to teach throughout my career, and have managed to do so in my retirement as a tutor with the Open College of the Arts and later as a group leader running art appreciation sessions for the University of the Third Age. Mostly it was teachers on in-service training courses. Sometimes it was students in training, and even when it was frowned upon by my employers it was often children in schools. In the authority in which I worked I found some schools were quite amenable to having someone from ‘The Education Department’ drop in to teach a few lessons, so I did, and they didn’t tell my bosses!

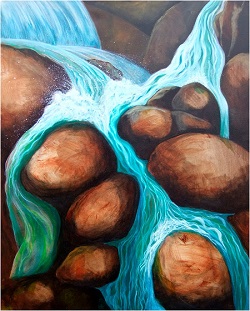

Even when I had highly responsible and busy jobs I never had to abandon art work completely. I’ve always kept sketch books and I draw every day, unless I’m ill! Then it was simply a matter of making use of whatever time I could put together. It’s not ideal but it can be workable.”

Perhaps the safest way to describe Mike Stevenson is as an artistic teacher, in every sense of both words. And I have learned not to judge a book by its cover – his scholarly articles have clearly been hiding a rebellious and creative man. Although, perhaps, it is possible to safely judge his book by its cover – you expect a funny and unruly book, and that is exactly what you get. As for the title, that too is exactly accurate.

“D’yer go to any of these exhibitions in art galleries?”

“Yes, I do”.

“Full of nudie pictures in them places, me Dad says. If you do nude paintings, Sir Lillian would probably strip off for yer. D’yer want me to ask her for you, Sir?”

“No I do not!” I snapped. “In fact, most of my paintings are landscapes, not figures at all. I don’t know where this rumour started”.